Gay people

Lesbian, gay and trans life in Germany began to thrive at the beginning of the 20th century. Berlin in particular was one of the most liberal cities in Europe with a number of lesbian, gay and trans organisations, cafés, bars, publications and cultural events taking place.

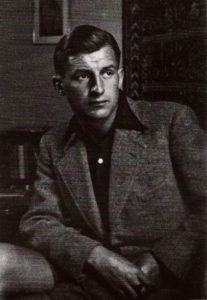

Albrecht Becker – imprisoned by the Nazis for being gay

By the 1920s, Paragraph 175 of the German Penal Code, which criminalised homosexual acts, was being applied less frequently. Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute for Sexual Science led the world in its scientific approach to sexual diversity and acted as an important public centre for Berlin lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender life. In 1929 the process towards complete decriminalisation had been initiated within the German legislature.

Nazi conceptions of race, gender and eugenics dictated the Nazi regime’s hostile policy on homosexuality. Repression against gay men, lesbians and trans people commenced within days of Hitler becoming Chancellor. On 6 May 1933, the Nazis violently looted and closed The Institute for Sexual Science, burning its extensive collection on the streets. Unknown numbers of German gay men, lesbians and trans people fled abroad, and others entered into marriages in order to appear to conform to Nazi ideological norms, experiencing severe psychological trauma. The thriving gay culture in Berlin was lost.

The police established lists of homosexually active persons. Significant numbers of gay men were arrested, of whom an estimated 50,000 received severe jail sentences in brutal conditions. Most homosexuals were sent to police prisons, rather than concentration camps, where they were exposed to inhumane treatment. There they could be subjected to hard labour and torture, or they were experimented upon or executed.

An estimated 10-15,000 men who were accused of homosexuality were deported to concentration camps. Most died in the camps, often from exhaustion. Many were castrated and some subjected to gruesome medical experiments. Collective murder actions were undertaken against gay detainees, exterminating hundreds at a time.

During the 1935 redrafting of Paragraph 175 in Germany, there was much debate about whether to include lesbianism, which had not been recognised in the earlier version. Ultimately lesbians and trans people were not included in the legislation and they were subsequently not targeted in the same way as gay men. In Austria, all same sex relations were criminalised and punishable under the penal code of 1852. This part of the penal code, which enabled persecution of gay and lesbian communities, was not amended during the Anschluss (the annexation of Austria into greater Germany under the Nazi regime) between 1938 and 1945.

After World War Two

After the war, the Allies chose not to remove the Nazi-amended Paragraph 175. Neither they, nor the new German states, nor Austria would recognise homosexual prisoners as victims of the Nazis – a status essential to qualify for reparations. Indeed, many gay men continued to serve their prison sentences.

People who had been persecuted by the Nazis for homosexuality had a hard choice: either to bury their experience and pretend it never happened, with all the personal consequences of such an action, or to try to campaign for recognition in an environment where the same neighbours, the same law, same police and same judges prevailed.

Unsurprisingly very few victims came forward. Those who did, even those who had survived death camps, were thwarted at every turn. Few known victims are still alive but research is beginning to reveal the hidden history of Nazi homophobia and post-war discrimination.