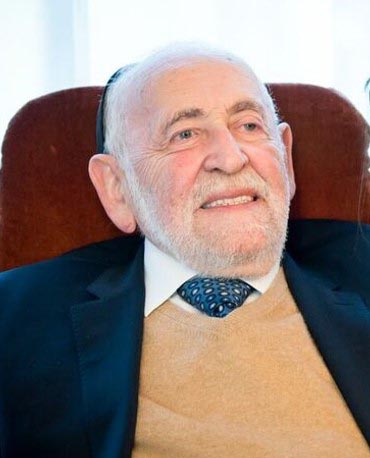

Yisrael Abelesz

Yisrael Abelesz was just 14 years old when he was deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau, the most infamous of all Nazi camps. Whilst there he escaped selection for the gas chambers and survived typhoid and a death march.

Lead image credit: Leivi Saltman Photography

Gradually, I realised what was happening because of the smoke from the chimneys and the smell of burning flies.

Yisrael Abelesz was just 14 years old when he was deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau Concentration Camp. He was born into an Orthodox Jewish family in July 1930 in Kapuvar, Hungary, a small town with a population of no more than 10,000 inhabitants and a Jewish community of around 500 people. His father owned a wholesale grocery business which gave the family a comfortable lifestyle.

In 1941, there was a dramatic change to their lives when Hungary allied itself with Nazi Germany. Many Hungarians sympathised with Hitler’s ideology, and antisemitism (anti-Jewish hatred) surged. Yisrael’s two older brothers were among the first to be sent to Jewish labour service in Hungary and later in the parts of the Soviet Union that were under German occupation.

In March 1944, Hungary fell under Nazi occupation and a full-scale assault on Jewish life commenced. The Jewish community was forcibly relocated and confined to designated areas, while also being subjected to the requirement of wearing a conspicuous yellow star to mark them out as Jewish. Yisrael’s father was among those impacted, as he was forced to shut down his shop. Subsequently, Jews were expelled from Kapuvar and relocated to Sopron Ghetto.

Shortly after Yisrael’s 14th birthday in July 1944, he, along with his two brothers, sister, and parents, were deported to Auschwitz. The journey lasted over three days in a cramped cattle truck, with little food or water. Upon arrival, Yisrael and his older brother were separated from the rest of their family by a man who he later learned was the notorious Nazi doctor, Josef Mengele. His younger brother and parents were immediately taken to the gas chambers and murdered.

‘I didn’t realise when my parents and brother were separated from me that I’d never see them again. I found out a few weeks later in the camp that they had been murdered in the gas chambers, but I didn’t want to believe it. Gradually, I realised what was happening because of the smoke from the chimneys and the smell of burning flies.’

Yisrael faced the terrifying prospect of being selected for the gas chambers not once, but twice. However, he was determined to do all in his power to survive. So, when the selection process targeted children, he quietly slipped away and found refuge in a secluded corner of the camp. No one pursued or searched for him.

When faced with the second selection, Yisrael once again escaped and hid among the Russian prisoners of war being housed in the camp. However, this time he was pursued by a kapo (a prisoner assigned to supervise other prisoners) overseeing the process. Remarkably, the Russians blocked the individual sent to fetch Yisrael from entering their barracks, allowing him to remain hidden until nightfall.

Yisrael and Judith on their wedding day

Recognising the pattern of selections occurring during daylight hours, Yisrael made a strategic decision to volunteer for daytime work in an attempt to evade being chosen for the gas chambers. With the help of a fellow prisoner employed in the camp’s kitchen, he was able to procure additional food rations. In 1944, Yisrael fell ill with typhoid, leading to a seven-week stay in hospital. After recovering, he was forced to donate blood to German soldiers.

As Allied troops made progress across Nazi-occupied Europe the prisoners were forced to walk to camps in Germany. As Yisrael marched, the Nazi officers announced that those in need of rest should step aside. Despite Yisrael’s fear of being shot for giving up, he had reached his breaking point and braced himself for an inevitable end. However, the exhausted prisoners were directed to a nearby camp. Yisrael recalls the words of the soldier accompanying them which gave him the strength to carry on: ‘Get your act together, you silly boy. We’re almost there.’

As soon as they arrived, he collapsed onto a bunk and fell into a deep sleep. It was only years later that he learned the place was called Althammer. Days passed before an announcement was made that they were moving again. Yisrael was determined to stay put and hid himself under a low bunk even as officers entered, shouting and issuing threats of violence. He suspected that the officers’ agitation stemmed from the anticipated arrival of Russian soldiers. Hours later, a sudden cry filled the air, proclaiming the arrival of the Russians.

Yisrael with his four children, daughter-in-law and her father / © Leivi Saltman

After liberation, Yisrael was reunited with three of his brothers and his sister, and together they embarked on the challenging journey of rebuilding their shattered lives. Yisrael and his wife Judith, another survivor from Hungary, made the decision to move to the United Kingdom in 1949. Together, they forged a new life and raised four children.

Yisrael pursued a career in the property sector while actively participating in London’s Golders Green Jewish community. He dedicated himself to the restoration of neglected Jewish cemeteries in Hungary, honouring the memory of those who perished.