The Kindertransport and refugees

The Kindertransport (Children’s Transport) was a unique humanitarian rescue programme which ran between November 1938 and September 1939. Approximately 10,000 children, the majority of whom were Jewish, were sent from their homes and families in Germany, Austria and Czechoslovakia to Great Britain.

Immediately after the Nazis came to power in 1933 the persecution of Jews began. This reached a pre-war peak with the November Pogrom (Kristallnacht) on 9/10 November 1938, when 267 synagogues were destroyed, 91 Jews were killed and 30,000 people were taken to concentration camps.

In response to this night of violence, British Home Secretary Sir Samuel Hoare agreed to speed up the immigration process by issuing travel documents on the basis of group lists rather than individual applications. Strict conditions were placed upon the entry of the children. Jewish and non-Jewish organisations funded the operation and had to ensure that none of the refugees would become a financial burden on the public. Every child had a guarantee of £50 to finance their eventual re-emigration. It was assumed at the time that the danger was temporary, and the children would return to their families when it was safe. Adult family members could not accompany the children.

The Movement for the Care of Children from Germany, later known as the Refugee Children’s Movement (RCM), sent representatives to Germany and Austria to organise transporting the children. On 25 November, after discussion in the House of Commons, British citizens heard an appeal for foster homes on the BBC Home Service. Soon there were 500 offers, and RCM volunteers started visiting these possible foster homes and reporting on conditions. They did not insist that prospective homes for Jewish children should be Jewish homes.

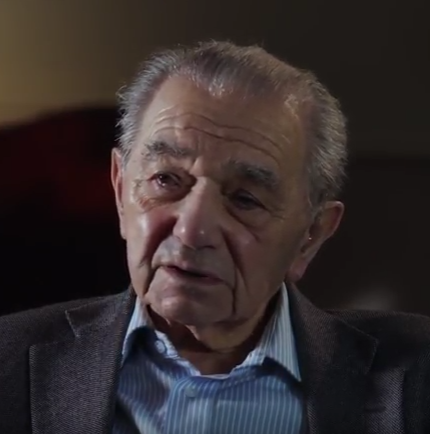

Kindertransport girls passing through customs © Wiener Library

The first Kindertransport from Berlin departed on 1 December 1938, and the first from Vienna on 10 December. In March 1939, after the German army entered Czechoslovakia, transports from Prague were hastily organised. Trains of expelled German Jewish children in Poland were also arranged in February and August 1939.

The last group of children from Germany departed on 1 September 1939, the day the German army invaded Poland and provoked Great Britain, France, and other countries to declare war. The last known Kindertransport from the Netherlands left on 14 May 1940, the day the Dutch army surrendered to Germany.

After the war ended many of the children stayed in Britain or emigrated to the newly formed state of Israel, America, Canada or Australia. Most of the children had been orphaned since leaving their homes, losing their families in the ghettos or camps they had escaped.

Refugees

Jewish refugees fled to Britain before the outbreak of war in 1939 to escape persecution, coming from Germany, Austria and Czechoslovakia. By 1939, Britain was home to over 60,000 Jewish refugees, 50,000 of whom settled permanently. They were joined after 1945 by a smaller group of Jews who had survived the Holocaust in Europe.

These refugees sought asylum from racial, religious and political persecution. Nazi measures against the Jews had not yet escalated into the attempt at total extermination that was to come. However, the vicious and systematic discrimination to which Jews were subjected made life intolerable for them even before 1939.

The admission of Jewish refugees to Britain was opposed by sections of the press, right-wing political forces including Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists, and by those arguing for the preservation of ‘British jobs’ at a time of high unemployment. The refugees had supporters in liberal circles and among those whose compassion was aroused by their plight. It was only after Nazi persecution of the Jews intensified in 1938/39 that Britain accepted larger numbers of refugees, admitting around 50,000 in the last eighteen months before the outbreak of war, including the 10,000 unaccompanied Jewish children who came on the Kindertransport.

The pre-war refugees from Germany were drawn largely from the Jewish middle classes and were well educated, cultured and often with professional qualifications or experience. They largely preserved their German-language culture and their ‘continental’ identity, while integrating broadly successfully into British society. The skills, enterprise and education that they brought with them ensured that they contributed significantly to British life. After the war most took British nationality and settled down to build new lives for themselves and their families.