HMDT blog: The Srebrenica massacre after twenty years

Dr Marko Attila Hoare is an Associate Professor specialising in the history of South East Europe, in particular of Yugoslavia, Serbia and Bosnia-Hercegovina at the Kingston University.

Marko Hoare

Prior to this he was a Research Fellow at the Faculty of History of the University of Cambridge, a British Academy Postdoctoral Research Fellow, a war-crimes investigator at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, and a research assistant at the Bosnian Institute in London. To mark 20 years since the Genocide at Srebrenica on 11 July, Dr Hoare looks at the international community’s response to these genocidal crimes over the last 20 years and explores how far the world has come in securing justice for the Genocide in Bosnia.

This week marks the 20th anniversary of the Srebrenica massacre of July 1995, when rebel Bosnian Serb forces carried out an act of genocide that claimed the lives of over 8,000 Bosniaks (Bosnian Muslims). In the interval, the world has come a long way towards acknowledging the crime. The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and the International Court of Justice (ICJ) have both recognised that genocide was committed at Srebrenica. The European Parliament in 2009 voted overwhelmingly for a resolution calling upon all EU member states to adopt 11 July, the anniversary of the start of the massacre, as a day of commemoration. Consequently, the UK held its first Srebrenica memorial day event in 2013, and is currently sponsoring a resolution at the UN to mark the 20th anniversary. Bosnian Serb officers have been found guilty by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and the Bosnian state court of genocide and other offences in relation to Srebrenica. The two leading Bosnian Serb perpetrators, Radovan Karadžić and Ratko Mladić, are currently on trial at The Hague for the genocide.

The world has come a long way, but from an ignominious starting point. The Srebrenica massacre did not come out of the blue; it was the crowning atrocity of a genocidal killing process that had begun over three years earlier, in the spring of 1992, and unfolded before the cameras of the global media. Not only did the international community – the United Nations (UN), European Union (EU), NATO and other bodies – not intervene to halt the genocide, but what intervention did take place made the situation worse. The UN maintained an arms embargo that hampered the ability of the fledgling Bosnian army to defend its citizens from the heavily armed Serb forces. The British and other Western governments resisted calls for military intervention to halt the killing, instead seeking to appease the perpetrators by accommodating their demands for the carving out of a Bosnian Serb territorial entity through the dismemberment of Bosnia-Hercegovina. Consequently, the Bosnian Serb leaders embarked on the massacre at Srebrenica in the fully justified belief that the world would not stop them, but would recognise their conquest of the town. UN officials blocked NATO air-strikes to defend Srebrenica, and the Dutch UN peacekeeping force supposedly defending this UN ‘safe area’ then abandoned or turned over to the killers the Bosniak civilians seeking their protection. The Dayton Accords that ended the war in November 1995 recognised the town of Srebrenica as part of Republika Srpska, the Bosnian Serb entity. Srebrenica was not just the shame of Serbia and the Serb nation, but the shame of Europe, the West and the world as well.

A ceremony at the Potočari-Srebrenica memorial (credit: Richard Newell)

For all the distance that the world has come, the journey remains incomplete. The International Court of Justice (ICJ) in 2007 found Serbia guilty of failing to prevent and punish the genocide at Srebrenica. Three years later, Serbia’s parliament narrowly passed a resolution recognising and apologising for the massacre. The resolution’s phrasing implied a recognition that genocide had occurred, but did not make this explicit, and Serbia’s leaders today remain unwilling to recognise the massacre as an act of genocide. The regime of Milorad Dodik, the president of Republika Srpska, denies the genocide outright and actively opposes all efforts at recognising it. This denialist stance has found support from Russia, which has joined Serbia in opposing the British-authored UN resolution. Meanwhile, the former Bosnian army commander in Srebrenica, Naser Orić, despite having been acquitted of war-crimes against Serbs by the ICTY, was recently arrested in Switzerland, on the basis of an international arrest warrant issued by the Serbian government. The latter has therefore signalled its determination to continue the fight against the Bosniaks of Srebrenica.

Momčilo Perišić, Chief of Staff of the Army of Yugoslavia (i.e. of Serbia and Montenegro) at the time of the Srebrenica massacre, was convicted by the ICTY in 2011 for his involvement in it, but was acquitted on appeal two years later, and to date no official or soldier of Serbia has been convicted over Srebrenica, or indeed for any war crime in relation to Bosnia-Hercegovina. The population of the town of Srebrenica itself, overwhelmingly Bosniak before the massacre, is today overwhelmingly Serb, and those Bosniaks who have attempted to return to it or to the surrounding area continue to face harassment from the Serb authorities. Yet it is a bitter irony for many Bosniaks that Serbia, the state responsible for arming and organising the Srebrenica perpetrators, will almost certainly join the EU before Bosnia-Hercegovina itself does.

Meanwhile, the wider responsibility of the international community remains to be fully acknowledged. Successful legal action brought in the Netherlands by the Srebrenica survivor Hasan Nuhanović established that the Dutch state was responsible for the deaths of three of his relatives in the massacre, and the level of compensation to which five relatives of these victims were entitled was agreed only last month, June 2015. These decisions open the door to further compensation claims by other survivors and relatives, but the process is still in its infancy. Meanwhile, Nuhanović was disinvited from a conference on Srebrenica at The Hague held last month by the Hague Institute for Global Justice and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, at the request of the Dutch organisers and participants, who would allegedly have felt ‘uncomfortable’ at his presence. The struggle in the West for justice and dignity for survivors is thus far from over.

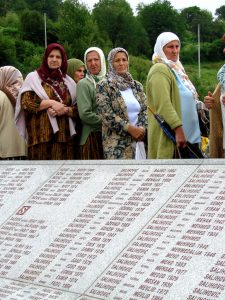

The Mothers of Srebrenica at the Srebrenica-Potočari genocide memorial (credit: Adam Jones)

Insofar as the Srebrenica genocide has achieved international recognition, this has paradoxically come at the price of the overshadowing of the wider killing process of which Srebrenica was merely the final phase. The Serb genocidal assault on the Bosniak population of Srebrenica and of Bosnia-Hercegovina as a whole began in 1992; in that year in the region of Podrinje (East Bosnia), where Srebrenica is located, more Bosniaks were killed than in 1995, the year of the final massacre. The mass killings, expulsions, torture and rape of men, women and children, involving the dissemination of hate-speech, organisation of concentration camps and the coordination of the Serb military and civilian authorities – all this was every bit as genocidal in nature in the regions of Prijedor, Zvornik, Visegrad and elsewhere in Bosnia-Hercegovina in 1992, as was the 1995 Srebrenica massacre. The latter represented the completion of the genocidal process begun in 1992. The Serb leadership’s decision to kill every single combat-aged male – broadly defined – that resulted in a much larger-scale massacre than had occurred in the Bosnian war previously, and that has marked the Srebrenica massacre as unique, represented a shift in its tactics but not in its goal, which was at all times to bring about the destruction of the Bosniaks as a group in the Serb-occupied areas of Bosnia-Hercegovina.

Courts in Germany that prosecuted the Bosnian Serb perpetrators Nikola Jorgić and Novislav Djajić in the 1990s established that genocide occurred in the Bosnian regions of Doboj and Foča in 1992, and the European Court of Human Rights, in its 2007 ruling upholding Jorgić’s conviction for genocide, ruled that this conviction was in accordance with the international legal definition of genocide embodied in the UN Convention. Yet because the ICJ ruled in 2007 that genocide had taken place only at Srebrenica, not elsewhere in Bosnia-Hercegovina, the misleading picture has emerged of Srebrenica as a local aberration; a ‘municipal genocide’. Scholars remain divided over whether it is correct to classify the mass violence across Bosnia-Hercegovina of the years 1992-95 as genocide or not, but this is above all a semantic question of a broad vs a narrow definition of the crime. The fact that the massacre at Srebrenica in July 1995 was part and parcel of a systematic process of mass killing and violence that began across the country three years earlier should be undisputed.

All of which is to show that however far the world has come toward recognition and justice regarding Srebrenica, there is still a very long way to go.

The HMDT blog invites guest contributors including academics, journalists and witnesses to provide personal perspectives on instances of discrimination, persecution and genocide. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of HMDT.

Find out more:

- Adam Boys was Director of the International Programs at the International Commission on Missing Persons. Read his blog about their work to identify the remains of the Bosnian War’s missing dead.

- Watch Besima’s testimony as she describes returning to the home she was forced from in Prijedor, and confronting the people farming her land.

- Read about the Srebrenica-Potočari Memorial Centre and Cemetery to the Victims of the 1995 genocide.

- Hasan Hasanović was 19 when the town of Srebrenica fell to Bosnian Serb forces in July 1995. Read Hasan’s life story.