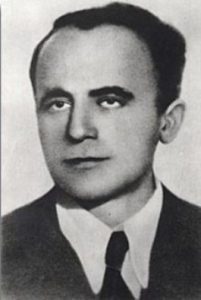

Emanuel Ringelblum and the Oneg Shabbat Archive

Born in 1900 in Buchach (which is now in Ukraine), Emanuel Ringelblum became a history teacher in Warsaw after completing his PhD on the history of the Jews of medieval Warsaw. He married Yehudis, and they had a little boy, Uri.

We reached the conclusion that the Germans took very little interest in what the Jews were doing amongst themselves… it was not surprising that the work of Oneg Shabbat could develop successfully

You can download a PDF version of the Emanuel Ringelblum life story here

Emanuel Ringelblum and the Oneg Shabbat Archive Welsh language life story

In October 1940, the Warsaw Ghetto was established. The Ringelblum family were rounded up and forced into the Ghetto, along with around 400,000 Jews from Warsaw and the surrounding suburbs. Although the Jews made up approximately 30% of the city’s population, the size of the Ghetto was only 2.4% of Warsaw. The conditions were extremely cramped, with an average of over seven people to each room, and with food being severely rationed by the Nazis, the outlook for those inside was bleak.

Emanuel took the initiative to create a secret archive to document the way the Jews were treated in the Ghetto. The archive was codenamed Oneg Shabbat, meaning ‘the pleasures of the Sabbath’. Emanuel said that the purpose of the archive was to ‘gather materials and documents relating to the martyrology of the Jews in Poland’. Many different people became involved and collected materials covering every aspect of their life in the Warsaw Ghetto, ranging from diaries, newspapers and official reports to posters, photographs, tram tickets and sweet wrappers. The documents were stored in milk churns and boxes and buried in three separate locations in the Ghetto.

In April 1943, Emanuel was sent by the Nazis to a labour camp, from which he escaped a few months later. He then went into hiding in an underground bunker in

Warsaw with his wife Yehudis, son Uri and 34 others, where he continued to write and gather information. The bunker was discovered by the Nazis in March 1944 and everyone hiding was murdered.

Only three people who had contributed to the Oneg Shabbat archives survived the war and in 1946 they were able to unearth one of the milk churns. A second churn was discovered four years later. The third milk churn has still not been found.

The archive is today listed on the UNESCO Memory of the World register, which lists documentary heritage of significance and outstanding universal value. The register aims to facilitate preservation, assist with universal access to the archive and to increase awareness.

The lid and one of the two milk churns in which portions of the Oneg Shabbat archives were hidden and buried in the Warsaw Ghetto

© Jewish Historical Institute

For more information:

- Read about the ghettos established by the Nazis

- YIVO institute for Jewish Research

- The War against the Jews 1933-1945, Lucy S. Dawidowicz, 1987

- The Years of Extermination – Nazi Germany and the Jews 1939-1945, Saul Friedländer, 2007