Hedy and her memory book

Hedy Klein was born in Oradea, in Romania, and was 16 when the Nazis entered her hometown, which had been absorbed into Hungary and renamed Nagyvarad. She was taken to Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp, and then worked as a slave labourer in a munitions factory. After the war, she left Romania illegally and went to Canada.

Big barrels of what they called soup was brought to us….We didn’t eat for three days, four days almost…but it was not a soup that you ever thought of as soup, it was what we know as dishwater, some kind of a liquid that had twigs in it and sand in it and pebbles in it…it tasted terrible and then I reminded myself if this is all we get, if there is some nourishment in it, I must force myself and drink it and so I held my nose and I cried and I swallowed and swallowed and swallowed.

Download Hedy Klein’s easy to read story

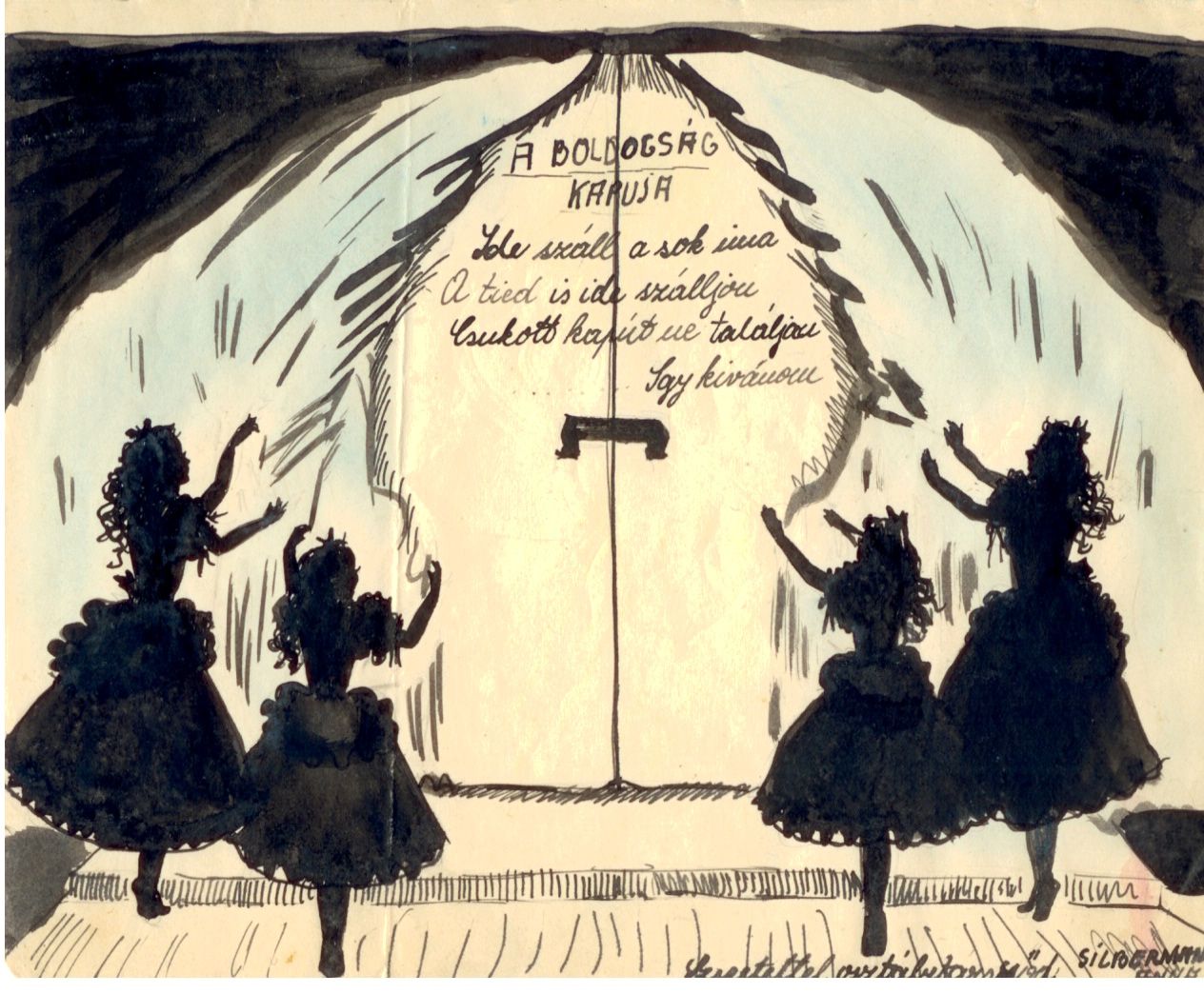

Hedy Klein was born in 1928, in the city of Oradea in Northern Transylvania, which at that time was part of Romania. Hedy was given a memory book as a birthday present when she turned 11, in 1939. Over the years her classmates, family and friends contributed poems, messages and drawings to the book in both Romanian and Hungarian.

Northern Transylvania became part of Hungary in 1940, and the Hungarian administration imposed restrictions on the rights of the Jewish population. The German Army entered Hungary in March 1944 and they together with Hungarian miltiary police constructed ghettos to contain the Jews. The Jews were only allowed to take a few necessities with them into the ghettos. Hedy gave her memory book to her Aunt Ilus, who, having married a Hungarian and been baptised, managed to avoid being taken to the ghetto. The conditions in the ghetto were arduous: Hedy and her family had to share a room with 15 people and there was limited food available to them. Hundreds of people were tortured in an attempt to discover where they had hidden their valuables; many of these people died from the beatings they received.

After three weeks the ghettos were emptied and Hedy was crammed into a cattle car with around 70 other people, including her parents. They were given just one bucket of water to drink between all of them and one bucket to use as a toilet. Three days later they arrived at Auschwitz-Birkenau; not everyone survived the journey. As Hedy and her parents got out of the cattle car, they were separated, Hedy tried to rejoin her mother but she was stopped. Hedy never saw either of her parents again; she was just 16 years old.

By the time she arrived at Auschwitz-Birkenau, Hedy hadn’t eaten for almost four days. She was eventually given a thinned down soup, containing sand, pebbles and twigs, rather than vegetables or meat. The soup, which Hedy compared to dishwater, tasted terrible, yet Hedy forced herself to drink it to get some nourishment.

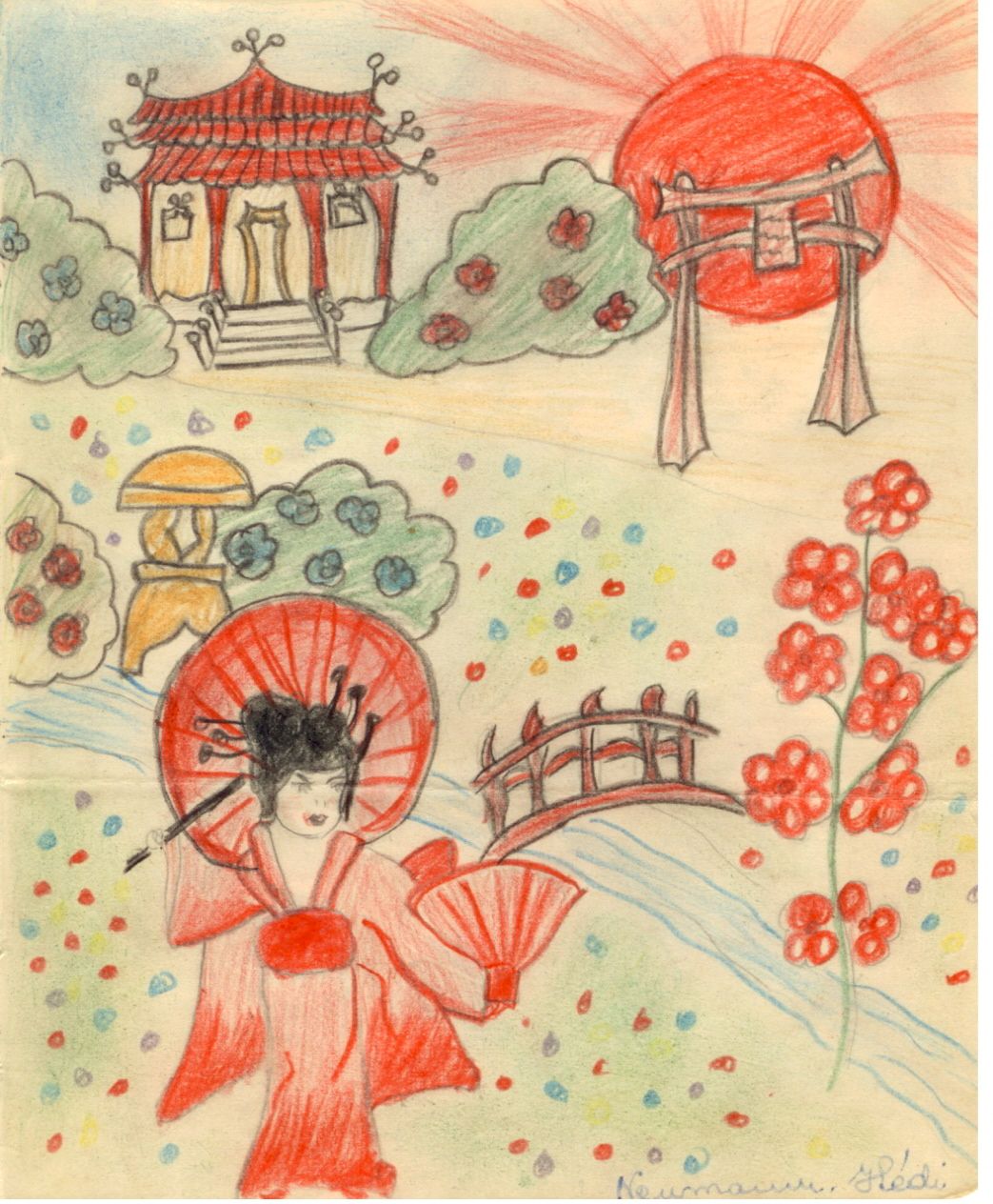

For the first time in her life, Hedy was separated from her family. In between roll calls, she and her fellow inmates were permitted to wander around the other barracks so Hedy used this as an opportunity to search for friends or family, and was able to find some of her classmates, including Mazso, who had drawn this picture for Hedy’s memory book:

Mazso came up to Hedy and asked her if she knew Mazso’s boyfriend, George. When Hedy replied yes, Mazso said ‘When you go home, find him, and tell him how much I loved him’. Hedy said, ‘why are you telling me that? You tell him that when you go home’. Mazso replied, ‘I know I won’t be home, I know I won’t make it, and I know you will’.

After a few dreadful months in Auschwitz-Birkenau, Hedy was transferred, together with her cousin, Eva, to a Volkswagen factory, in Fallersleben, in Germany, where she worked as a slave labourer making munitions. While the conditions in the factory were marginally better than at Auschwitz, the factory was not heated and Hedy and Eva had little clothing.

American troops liberated prisoners including Hedy and her cousin Eva in April 1945 and the troops encouraged them to go into the local town and take anything they needed. Hedy and Eva chose one dress each and were then taken to a refugee centre, which was near the former concentration camp at Bergen-Belsen. After a few weeks, transport was arranged to take Hedy back to Oradea, which was now Romania again, because the Soviet and Romanian forces had pushed out the German and Hungarian troops.

In 1944, there were almost 30,000 Jews in Oradea. Only 2,000 survivors returned after the Holocaust: neither Mazso nor Hedy’s parents were among them; they had been murdered by the Nazis. Hedy was subsequently looked after by her Aunt Ilus, and she was reunited with her memory book.

A few years later, aged 19, Hedy fell in love with Imre Bohm, whom she had met years earlier at a school dance. They married at the end of 1947 and decided to leave Romania illegally, knowing that a communist regime was coming shortly. They travelled through Hungary to Czechoslovakia, and they had to leave Hedy’s memory book behind. In Czechoslovakia they stayed with another of Hedy’s aunts, and applied to many different countries for visas. Canada was the first country to grant them visas, and Hedy and Imre went there, arriving in 1948. Hedy found a job in a factory, and then she worked in an office, before becoming a shopkeeper together with her husband Imre. Hedy sent money and food parcels to her aunt Ilus in Oradea, and in the 1960s Hedy was able to return to Oradea to see her aunt and to collect her memory book. Hedy and Imre had two children together and were successful in their business, opening up three stores.

A few years later, aged 19, Hedy fell in love with Imre Bohm, whom she had met years earlier at a school dance. They married at the end of 1947 and decided to leave Romania illegally, knowing that a communist regime was coming shortly. They travelled through Hungary to Czechoslovakia, and they had to leave Hedy’s memory book behind. In Czechoslovakia they stayed with another of Hedy’s aunts, and applied to many different countries for visas. Canada was the first country to grant them visas, and Hedy and Imre went there, arriving in 1948. Hedy found a job in a factory, and then she worked in an office, before becoming a shopkeeper together with her husband Imre. Hedy sent money and food parcels to her aunt Ilus in Oradea, and in the 1960s Hedy was able to return to Oradea to see her aunt and to collect her memory book. Hedy and Imre had two children together and were successful in their business, opening up three stores.

After Imre died in 1992, Hedy decided to talk about her experiences during the Holocaust, specifically to try to counter antisemitism (anti-Jewish hatred) and prejudice. Together with her memory book, Hedy has been to a number of Canadian schools to share her story in order to educate young people about the dangers of prejudice and discrimination.

This resource has been prepared with the support and co-operation of www.tikvah.ro