Marianne Grant

Marianne Grant was a young artist from Prague. Having survived Theresienstadt, Auschwitz-Birkenau, and the final days of Bergen-Belsen concentration camps, using her skills as an artist to survive, she came to Glasgow where she raised her family.

News travelled fast, and I was ordered to Mengele… He paced up and down in his high leather boots without a word. I was shaking. If I had made a blob or mistake, I would have been finished. At this time, I knew I was painting for my life.

Marianne Grant, known as Mausi, was born in Prague to Rudolf and Anna Hermann in September 1921. Her father was the foreign exchange manager of the Bohemian Union Bank and her mother was a milliner.

She attended primary school and later a private English grammar school. Instead of paying attention to her teachers, she would draw under the tables during lessons. After much persuasion from her father’s sisters on her behalf, her father finally gave her permission to attend the Rote Schule of Fashion and Graphic Design in Prague. She had originally intended to continue her education at the prestigious Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design in Jerusalem however Marianne gave up her place after her father died in 1938 so she could remain in Prague with her mother.

A few months after Rudolph died, the Nazis invaded Czechoslovakia. Marianne and her mother had to leave their flat and move to the other side of the river.

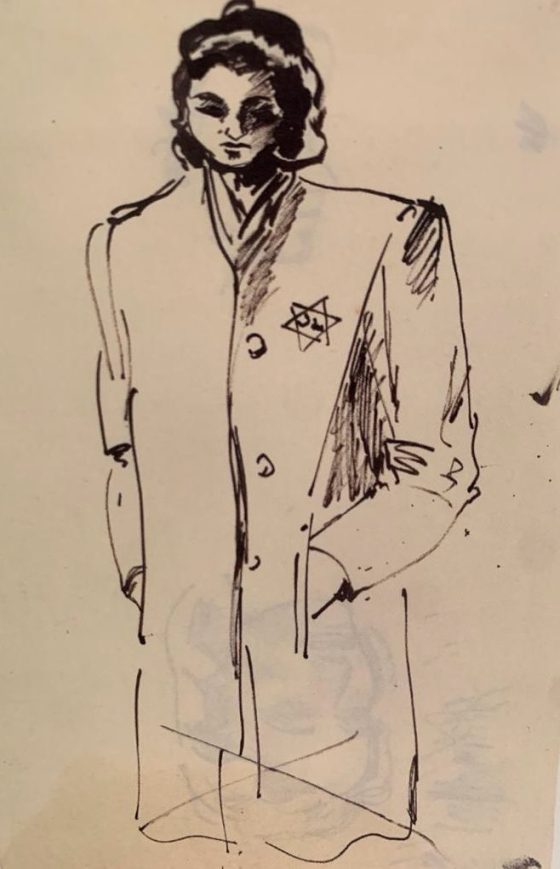

Later, they were forced to wear a yellow star on all their clothing to indicate they were Jewish. To earn some money, and help to provide for herself and her mother, Marianne secretly taught Jewish girls to sew.

In April 1942, Marianne and Anna were sent to Theresienstadt, a ghetto and concentration camp 30 miles north of the city. They were forced to sleep in overcrowded rooms with 40 other people, putting up sheets as dividers for privacy. Marianne had brought her art supplies and featured the hanging sheets in her art.

Whilst in Theresienstadt, she worked in agriculture as she had heard that she would be able to procure more food there, both to eat herself and to trade for other goods.

Marianne became a leader of the youth garden where she took care of 12-17 year old girls working alongside her. Later, she and her friend Gert would visit what she called the ‘mock cafes’, created as propaganda, to practice drawing people. Even in the ghetto, she was practicing and honing her art skills.

Deportations to the east started to become more frequent. Marianne managed to prevent her mother from being deported on three occasions, but it was not possible to protect her forever. Having left her artwork with a friend, Marianne left Theresienstadt with her mother and was sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau.

At Birkenau, Marianne was sent to work in the children’s block, looking after children who had been separated from their parents. Using what materials she could find, she taught the children art. Having spotted her talent, one SS officer asked her to make hand painted story books for his children, and later took her to paint a young Roma woman as a present for his wife. After Marianne fell ill with pleurisy, the SS officer demanded to see the Jewish doctor for the block. When no medicine could be provided, he brought Marianne additional bread and butter for her, likely saving her life.

News of Marianne’s artistic talent spread in the camp, and she was later summoned to SS physician Dr Josef Mengele who conducted inhumane, and often deadly, medical experiments on prisoners at Auschwitz. She was ordered to draw the family trees of his victims and the markings on the bodies of twins subject to his experiments. After this, Marianne gained permission to draw on the walls of the children’s block. She recreated her mural – featuring Mickey Mouse, Bambi and nature – for Yad Vashem’s No Child’s Play exhibition in 1997.

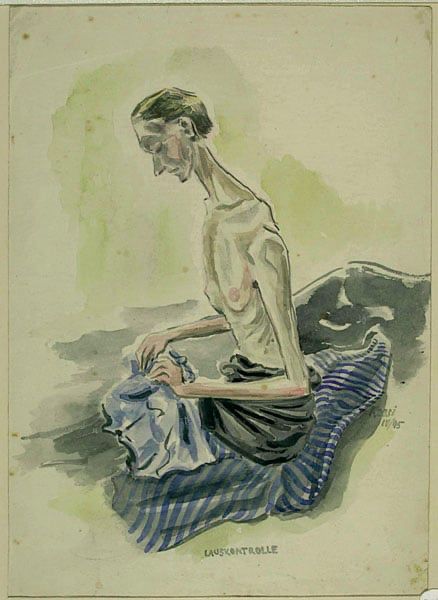

As the war went on, deportations took place, taking prisoners from camps into Germany. Marianne was sent by cattle-wagon to Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp, 10 days before its liberation. Before being sent to Bergen-Belsen, Marianne was ordered to decorate the walls of the officer’s dining halls with pictures of beer jugs and food. As a result, she was allowed to keep her art materials, meaning when she arrived at the camp, she documented what she saw.

Marianne being awarded the Freedom of East Renfrewshire

Bergen Belsen was liberated on 15 April 1945 by the British Army. Her mother contracted and survived typus. Marianne got a job as an interpreter for the British Army and then a couple of months later her and her mother were transported to Sweden by the Red Cross. Marianne met her future husband Jack through a friend who had put them in touch as pen pals, and in 1951 they were married in London before moving to Scotland where they settled. Marianne and Jack had three children, Geraldine, Susan and Gary.

Marianne’s drawings remained locked in a trunk for 50 years, before she donated them to Glasgow Life, part of Glasgow City Council. A selection of her pieces are now on permanent on display at Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum in Glasgow, and her catalogue of works is available to see in a book published in 2021 titled Painting for My Life: The Holocaust artworks of Marianne Grant.