Otto Rosenberg

Born in 1927, Otto Rosenberg grew up in Berlin with his grandmother and two siblings. His family were Sinti, a Romani population of central Europe. Otto remembers living on private rented ‘lots’ of land that his family shared with the caravans and houses of extended family and other members of the Sinti community.

The children… bumped into me and called me names, that I was a dirty gypsy and much more.

You can download the PDF version of Otto Rosenberg’s life story here

Otto Rosenberg’s easy to read life story

‘On the lots we were all just one big family. Everybody knew everybody.’

During the 1930s, the Roma and Sinti populations in Germany and across Europe faced appalling prejudice and discrimination. Otto was no exception, especially at school.

In 1936 the Nazis ordered the forcible relocation of all Roma and Sinti in Greater Berlin. Otto and his family were sent to Berlin Marzahn Rastplatz, the first internment camp for the Roma and Sinti in Nazi Germany.

Aged 13, Otto was drafted into a company making shells for submarines. Initially he enjoyed his work, however in spring 1942 his rations were cut and he became excluded from the rest of the workforce at meal times.

‘I was… no longer allowed to sit at the breakfast table… I had to eat my breakfast outside on a timber pile in the yard… Many people were sorry about this… But there were also many others whom this did not bother at all.’

One day, after picking up a magnifying glass he found, Otto was arrested and was unfairly accused of sabotage and theft of military equipment by the Nazis. He was transported to prison where he spent four months alone in a cell without a trial.

In December 1942, the Nazis ordered many of those who were part Sinti or Roma were to be transported to Auschwitz. Otto was visited in prison by a relative who told him that his family had been moved.

At his trial Otto was found guilty of the crimes put against him but was released having already served his time. Yet he was not to be a free man. Barely through the prison gates, Otto was arrested and put on to a train. Shortly before his 16th birthday, he arrived at Auschwitz.

‘Sorting began immediately. The Jews over there, the Sinti over there, the Poles over there and so forth. Everything was organised. You were taken to a doctor. He gave a signal, mostly with a bell… You had to roll up your sleeve and a Pole – his name was Bogdan – tattooed a number on your arm with a sort of pen. Z 6084 was my number.’

After a few days Otto was moved to the so-called Gypsy camp in Auschwitz-Birkenau, where many of his family members were held, including his sister and grandmother. Day-to-day life in the camp was unimaginable, that of beatings, starvation, work, sickness and death.

‘I do not know whether today if I were to walk by a pile of corpses I would be totally without feelings, but at Birkenau I had got used to it. The corpses were part of our daily routine.’

After a failed attempt to liquidate the so-called Gypsy camp at Birkenau, the decision was made to transport many of those who were still able to work to other camps. At first Otto did not want to leave his grandmother – but she told him that he must go while she stayed with children who had lost their parents.

On 2 August 1944 Otto and 1,407 others were loaded on to a train which left for the Buchenwald concentration camp at around 7pm. That same evening SS guards surrounded all those remaining at the so-called Gypsy Family Camp, loaded them on to lorries and drove them to the gas chambers where they were murdered.

From Buchenwald, Otto was moved to Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp, then to Bergen-Belsen where he was liberated by British troops along with 60,000 other prisoners. He soon found himself admitted to a hospital to recover.

‘After several weeks I already felt much stronger again. The fear which still breathed down the back of your neck had lessened, the feeling of being murdered and burned. Now we looked about us. We found the danger is over for the time being. We are safe.’

The effects of persecution at the hands of the Nazis played a major part in Otto’s life.

‘Why did I survive? I do not know the answer to that myself… They say: you have your freedom now, be happy. There was no way I could be all joyful, because I missed my brothers and sisters, always, to this very day. When the holidays came and people celebrated, or the families sat together, that was when this inner thing, this nervous strain came. That was very hard.’

Once physically strong enough, Otto slowly began to make his way back to Berlin in search of family, friends and somewhere to call home. In time he found his aunt and mother who had been in Ravensbruck concentration camp. He began to rebuild his life and worked re-building the city.

In 1970, Otto founded what is now known as the Berlin-Brandenburg State Association of German Sinti and Roma. He was the chairman of the association until his death. In 1998, he received one of the highest state decorations in Germany for his work on behalf of the Sinti and Roma people. In 2007, a street and a square in the grounds of the former Berlin Marzahn camp were named after him.

Otto died in 2001, father to seven children and husband to a wife he married in 1953 at a ceremony ‘With peonies, but without a big ado, with potato salad, and a little bit to eat and drink.’

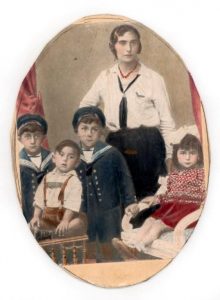

Otto (front) with (left to right) his brothers Waldemar and Max, mother Luise Herzberg and sister Therese.

This resource has been produced with support from Petra Rosenberg, Otto’s daughter, for which we are very grateful.

Otto Rosenberg’s quotes are from his book, A Gypsy in Auschwitz, published in 1999.

For more information:

- Read about Berlin-Brandenburg State Association of German Sinti and Roma online here (German language website).

- Find out more about Nazi persecution of other groups.