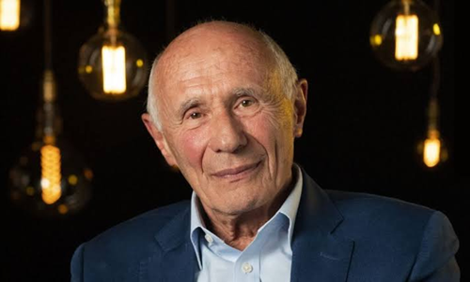

Peter Lantos BEM

By the age of 30, Peter Lantos had endured the horrors of Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, lost most of his family, suffered abuse at the hands of Hungary’s Communist police, earned a medical degree and defected to England.

Lead image credit: Holocaust Learning UK

Antisemitism, the hatred of Jews which fuelled the Holocaust, is alive and well everywhere, including this country. This is the reason why I decided to tell my story to younger generations.

Peter Lantos was born on 22 October 1939 in Makó, a small provincial town in southeastern Hungary. His maternal family owned a timber yard managed by two of his uncles who lived in adjoining villas on the property. In contrast, Peter’s immediate family resided in a modest annex at the back.

Peter as a young child

In 1944, following the German occupation of Hungary, a wave of antisemitic laws was enacted. Peter’s 18-year-old brother was taken away for forced labour and never returned. Shortly afterwards, the family was forced into the ghetto in Makó where they remained for several weeks. In the summer of 1944, at the age of five, Peter was deported to Bergen-Belsen in northern Germany with his parents – simply because they were Jewish. His happy childhood was abruptly shattered – he lost his toys, his home and his friends.

The safe, familiar world he knew vanished, replaced by uncertainty, despair, disease, hunger, cruelty and starvation – and, ultimately, by the death of those around him.

Upon arrival, Peter became prisoner number 8431. He and his mother were separated from his father, and, with each passing day, life grew more unbearable. Bread rations dwindled, standing for roll call in the icy wind became increasingly torturous and disease spread rapidly through the camp. There was no place for children to play or form friendships; instead, they were forced to witness constant cruelty and death. Though Bergen-Belsen was not an extermination camp – there were no gas chambers – it became a ‘hell on earth’ through starvation, disease and relentless suffering.

Severe overcrowding, starvation and lice created ideal conditions for the spread of disease. Typhus, typhoid fever dysentery and tuberculosis were rampant and uncontrolled. Peter’s father died of starvation just four weeks before the British Army liberated Bergen-Belsen on 15 April 1945. After surviving the camp, Peter and his mother returned to Hungary but it was far from a joyful homecoming.

Peter with his mother Ilona soon after their return from Bergen-Belsen

They learned that 21 members of their family had been murdered. His brother had died of typhoid fever only a month before their return. Witnessing such immense suffering as a child was a decisive factor in Peter’s decision to become a doctor. Initially, his plans to study medicine were blocked by the Communist authorities who labelled him ‘alien class’. However, his mother successfully challenged the classification, and he was eventually allowed to pursue his studies. After qualifying, he was fortunate to receive a research fellowship in 1968, which enabled him to work in London.

As the one-year research fellowship neared its end, Peter made the decision not to return to Hungary, driven by political, professional and personal reasons. In response, the Hungarian authorities sentenced him in absentia to 16 months in prison and ordered the total confiscation of his possessions. He would not set foot in his homeland again until after the fall of Communism in 1989.

Peter’s career in academic medicine in England spanned more than three decades, during which time he made significant contributions to the understanding of neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. His work gained international recognition, and he was elected a Fellow of the Academy of Medical Sciences.

Peter’s career in academic medicine

Peter only fully grasped the significance of his Holocaust experiences during his teenage years. Despite this, he chose not to carry the psychological burden of these memories and believes he has succeeded in doing so. He decided to learn German at school and, as soon as he had the chance, travelled to East Germany as a medical student. There, he made German friends, which helped him overcome feelings of hatred. He described this openness as an effort to understand what happened and how it could have happened.

In retirement, Peter has published books for both adults and children that draw on his experiences during the Holocaust. He remains deeply engaged in Holocaust education, working to ensure that its vital lessons are not forgotten.

Antisemitism, the hatred of Jews which fuelled the Holocaust, is alive and well everywhere, including this country. This is the reason why I decided to tell my story to younger generations, in the hope that by learning from it, they might also reject hatred, intolerance and discrimination, says Peter.