Yvonne Bernstein

Yvonne Bernstein was one of thousands of Jewish children hidden across Europe during the Holocaust. Her identity disguised, she was able to survive, avoiding the fate of 1.5 million Jewish children who were murdered by the Nazis.

Being a hidden child during the Holocaust was a distressing experience; we lived in constant fear.

Image: Photograph of Yvonne taken by the then Duchess of Cambridge © Kensington Palace

By Yvonne Bernstein

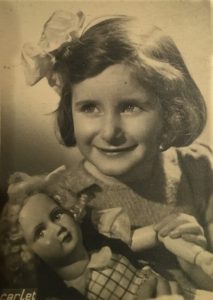

Yvonne as a child

I was born as Ursula Mayer in Pforzheim, Germany, where my father, Martin, ran a family jewellery and silverware business. However, the Nazis seized the firm in July 1938, forcing my father into a temporary role as a travelling salesman. It was whilst he was on a business trip to Holland on 9-10 November 1938 that Jewish businesses, homes and synagogues in Germany were violently attacked.

Dozens of Jews were killed, and thousands more were rounded up and taken to concentration camps. The November pogrom (Kristallnacht) was a crucial moment that would eventually lead to the Holocaust. Given the gravity of the situation, my father heeded the advice not to return to Germany. He was eventually given a visa to England and arrived in April 1939.

A month later, my mother also received a domestic labour visa to join my father. The promised visa for me did not arrive. My mother was told to put me in an orphanage, but instead, she entrusted me to her sister, who lived in Lorraine, France, with the hope that it would be a temporary arrangement lasting only a few weeks. My visa did not arrive, and war broke out. By then, my tears had dried, and I called my aunt ‘Maman’ (mother in French), and my cousin Nicole was like a sister to me.

The Yellow Star of David

In July 1940, the German army entered Sarrebourg, the garrison town where we lived, and my aunt was given 24 hours to vacate her home and leave the town with me, aged three, my cousin aged five, and her senile mother-in-law (my uncle, Gaston Bloch, was at that time still in the French army). A neighbour, seeing her plight, took us to Luneville where we boarded a train to Paris to stay with family.

After being discharged from the army, my uncle joined us in Paris, obtained a job and secured new accommodation for us. I attended school with Nicole and forgot about my parents. I felt like a truly spoilt child.

In 1942, my uncle refused to comply with the decree ordering all Jews over the age of six to wear the yellow Star of David. However, everything changed on 17 January 1944 when a police officer arrived and took us to Drancy, where Jews were being rounded up for deportation.

Nicole, my aunt, and I were released and to this day I have no idea why, but it is possible that my uncle bribed the police to ensure our safety. In the event, my uncle was arrested and taken to Auschwitz-Birkenau, the largest and most infamous Nazi death camp, where he was murdered.

Life as a hidden child

With the help of non-Jewish friends, we were at first hidden in a warehouse, and then Nicole and I spent two months in a convent while my aunt was given false papers for us under the (French) names of Yvonne, Nicole and Hélène Blanc – changed from Ursula, Nicole and Herta Bloch.

Being a hidden child during the Holocaust was a distressing experience; we lived in constant fear, an unguarded comment or the suspicions of nosy neighbours could lead to discovery and death.

How my father found me

Yvonne with her father

By the time Paris was liberated by US forces in August 1944, my father had joined the British Army and served in the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers Corps. He was stationed in Bayeaux, northern France, and when the Americans liberated Paris on 25 August, he was given permission to look for me.

My aunt was aware that none of the family knew our assumed names or address, so she went back to our old (pre-arrest) apartment and left our details with the caretaker. That is how my father was able to find us. It took time before I could accept my father because we had been apart for six years.

In May 1945, I was given a visa to enter England. My aunt – who I regarded very much as my mum – prepared me to meet my ‘mummy’ and new brother, who was born in England during the war. Even so, it was not so easy for me to blend into another home. My mother was of course delighted to see me, but my two-year-old brother was upset at having to share his mother’s attention with me, especially as I only spoke French when I first arrived (my mother spoke German and English).

I learned English quickly but never revealed my German origins to anyone at school. I was known as the ‘French Girl’. My aunt and cousin were able to get visas to come to England and lived with us from 1947 to 1956, which made me very happy. Later, as an adult, I ventured to London in search of fresh opportunities and experiences. I married my husband Leo and had three children.

Photographed by the Duchess of Cambridge

Photograph of Yvonne with her granddaughter, taken by the then Duchess of Cambridge © Kensington Palace

In 2020, as part of a project to mark the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau, I had the honour of having my portrait taken by the then Duchess of Cambridge at Kensington Palace. Generations: Portraits of Holocaust Survivors, featured 75 images of Holocaust survivors and their family members and first opened at Imperial War Museum London in August 2021.

The photograph captures me standing next to my granddaughter, Chloe, while I hold a brooch and an identification card dating back to 1939, bearing a prominent ‘J’ stamp, which was used by the Nazis to indicate I was Jewish.

Having dedicated much of my post-retirement life to Holocaust education and commemoration, I was greatly honoured to receive an MBE in 2022. The significance of royal support for survivors and the recognition of the Holocaust’s historical truth cannot be overstated.